Road. (n.) A wide way leading from one place to another, especially one with a specially prepared surface that vehicles can use. “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.” Lewis Carroll

The first great roadbuilders, and engineers, were the ancient Romans, and parts of their roads survive to this day, over two millennia later. In the interim, the prepared surfaces of engineered roads have been made of mud, clay, brick, stone, and even wood block. Yet, for over a century now, by far the most common durable road surface has been the familiar black cement-and-aggregate mixture known as hot-mix asphalt. Other English-speaking parts of the world know it as bitumen, or macadam.

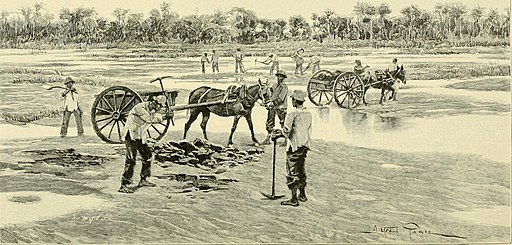

This asphalt, first mined from pitch lakes on the island of Trinidad and similar deposits around the world, was originally mixed with gravel by hand labor in large metal trays placed over direct fire. Hard, hot work. As this natural asphalt became replaced over the years with an engineered formula derived from crude petroleum, both the heating process as well as the mixing technology evolved rapidly. Early mixers were adapted from the rotating drums used for cement mixing. And by the 1920s or 1930s, some asphalt producers, supplying material for both roadbuilding and for other uses such as roofing and pipe-dipping, had begun to use indirect heating to improve the uniformity and consistency of the end-product, as direct heat could be difficult to control. A 1931 technical article in The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry mentions steam, diphenyl vapor, and hot oil among the heating media already in use for indirectly heating asphalt tanks.The evolution continues to this day. The hot oil that those pioneers used back in the 1930s to heat asphalt tanks was a lubricating-oil base stock, designed not for heating but to protect metal surfaces and extend the life and improve operation of rotating equipment. These days, modern heat-transfer fluids are engineered specifically for high temperature service, and are derived from a variety of chemical families for rugged service, long life, and resistance to thermal and oxidative deterioration.

The heating equipment itself has also evolved a long way from those simple heated trays stirred by hand with long metal hoes. In the 60s producers moved beyond hot-oil heated asphalt plants, adding surge bins and storage tanks to allow more flexibility in meeting variations in demand. Innovators continued to develop other ways to extend the workability time and distance range of the product going out of the plant hot and ready for roadbuilding. Today, information systems, and advances in integrating computer systems into testing, supply, heating, environmental controls, and logistics are adding a whole new level of sophistication to asphalt plant operations.

Paratherm—Heat Transfer Fluids and the Asphalt Industry OEMs

Paratherm works together with the asphalt construction equipment OEMs to help their customers, and ours, to keep their systems maintained, up and running, especially when it counts the most.

It’s August, and in North America, the paving season is at its apex for 2016.

Among the equipment specialists in the asphalt-paving industry is Meeker Equipment Company Inc., which manufactures components to upgrade, renovate, and retrofit existing asphalt and ready-mix plants.

I spoke earlier this month with Jeff Meeker, President of Meeker Equipment, about this year’s paving season.

“We hear from our customers that generally speaking the paving season is going very well,” Meeker said. “Certain areas see a bit of trouble, usually related to political issues. New Jersey in particular needs attention to their transportation trust fund, so there’s a slowdown there at peak season.”

“We also see a lot of paving companies reinvesting in their asphalt plants,” Meeker emphasized. “Money that had been sitting on the sidelines is now going back into rebuilding their businesses.”

I asked Jeff for his opinion about of the evolving role of indirect heating, and specifically how the heat transfer fluids can be a key to preventive maintenance in the manufacturing process.

“Well, our people have become more plugged into talking to construction companies about their hot oil in these equipment discussions, and how important it can be for their operations,” Meeker explained.

“These days, when we visit our customers, our people always carry a heat-transfer-oil test kit,” Meeker said. “The plant managers and maintenance men are increasingly realizing the value of their hot-oil equipment, its impact and importance for their asphalt plants. So we can give them a test kit right there and get them started to evaluate the condition of the system based on the oil test results.”

If you’re an asphalt processor, and you’re interested in a fluid analysis kit, you can get one when the Meeker rep stops by. Or, here at Paratherm, there’s an online form you can fill out and we’ll send you one right away. Here’s the link: Fluid Analysis Kit.

and history of the PA Turnpike, its abandoned tunnels and planned modern renewal, and the engineering feat that took it through (not across)

Pennsylvania’s Appalachian Mountains. Here it is— Ghost Tunnels of the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Haunting photography, too.